I grew up in suburban New Hampshire in one of the best public school systems in the state. I loved learning. I was a sensitive kid, and valued the opinions of those above me extremely highly, which motivated me to always perform at my best capacity. In 12 years, I had over 60 distinct classes with over 40 teachers. I still remember the feeling of anticipating an exam, the gulp lodged in my throat before giving a presentation, the wave of reward at scoring well, receiving praise, mastering a topic. School was emotion, discovery, a hierarchy of social and intellectual capabilities, a world in and of itself. It was my life.

College irked me. What my K-12 teachers did so well to inspire me, few of my college professors seemed to have a grip on. I discovered that concepts without fun were a drudge to learn. I found learning itself to be like an egg squeezed from every angle; pressure from my professors and my textbooks and my friends who had always seemed to pick up concepts much easier than I could. I didn’t speak the language of the other engineering students. I experienced fear of failure for the first time in my educational journey, and it ate me alive. I was trained to operate at a minimum threshold of understanding something in order to become a hungry learner for more. Without that skill cushion that I hadn’t even realized I depended upon in K-12, I felt like I was flailing through the air with a parachute in my hand but didn’t know how to use it.

I didn’t know how to grapple with learning at a starting point of 0. It was for this reason that I couldn’t get myself to learn things that interested me but which possessed necessary skillsets beyond what I currently had, like computer science. I was incapable of grappling with discomfort. I didn’t know how to grapple with learning in the absence of built-in community, with having to forge that for myself if I wanted it. I finally understood why some other high schoolers didn’t take school as seriously as I did. Ashamed of my apparent lack of control on my education, I became a mediocre student. I felt more like a data point on a registry than a person. I still valued the opinions of my teachers highly, and that made my lack of knack in the subjects sting even more. I’d study to regurgitate for exams then forget the concepts a few weeks later, which started biting me in the ass when the engineering courses compounded. Luckily I could evade this compounding with the loopholes that Covid-hybrid classes allowed for. I wasn’t truly learning, and I was feeling an emptiness inside of me like an inflated ballon that would never pop. I wasn’t deriving happiness from school anymore and I couldn’t tell if it was my fault or the world’s. The scholar in me was dead. This realization was one of the hardest pills I’ve ever had to swallow.

I wasn’t unhappy in college, of course. Everyone would tell you the exact opposite. I found solace in doing the things where I could be a big fish in a small pond again, which primarily involved engaging with the entrepreneurship scene on campus. Here was a community I spoke the language of, programs I had a background in, learning that felt fun. Here, I could be confident.

It was during this period of effusing into the entrepreneurship community like wildfire that I realized what a core part of the equation confidence plays — every one of the greatest moments of my life was derived from one confident moment, one leap of faith that led to the unlocking of something great, either by someone I met or a skill that I learned. But learning in the absence of confidence was utterly impossible. So, in college and as a kid who could not yet handle the discomfort of starting from 0, I doubled down in what I knew was working. I interned at companies in manufacturing operations roles, since that’s what I’d done before. I led clubs and organized online fellowships, since I had a knack for that, too. I was always learning and always working every single day for hours on end at my laptop, though did so in a comforting kind of learning in which I doubled down in my strengths instead of trying to build new foundations of knowledge in other domains.

I reaped the benefits of verticalizing my talents. I became well known fast. I had the confidence to do anything I wanted to, so long as it was within the realm of my minimum viable domain expertise. I was unstoppable, when I swam in the lanes I knew.

This, I believe, is where America’s downfall begins.

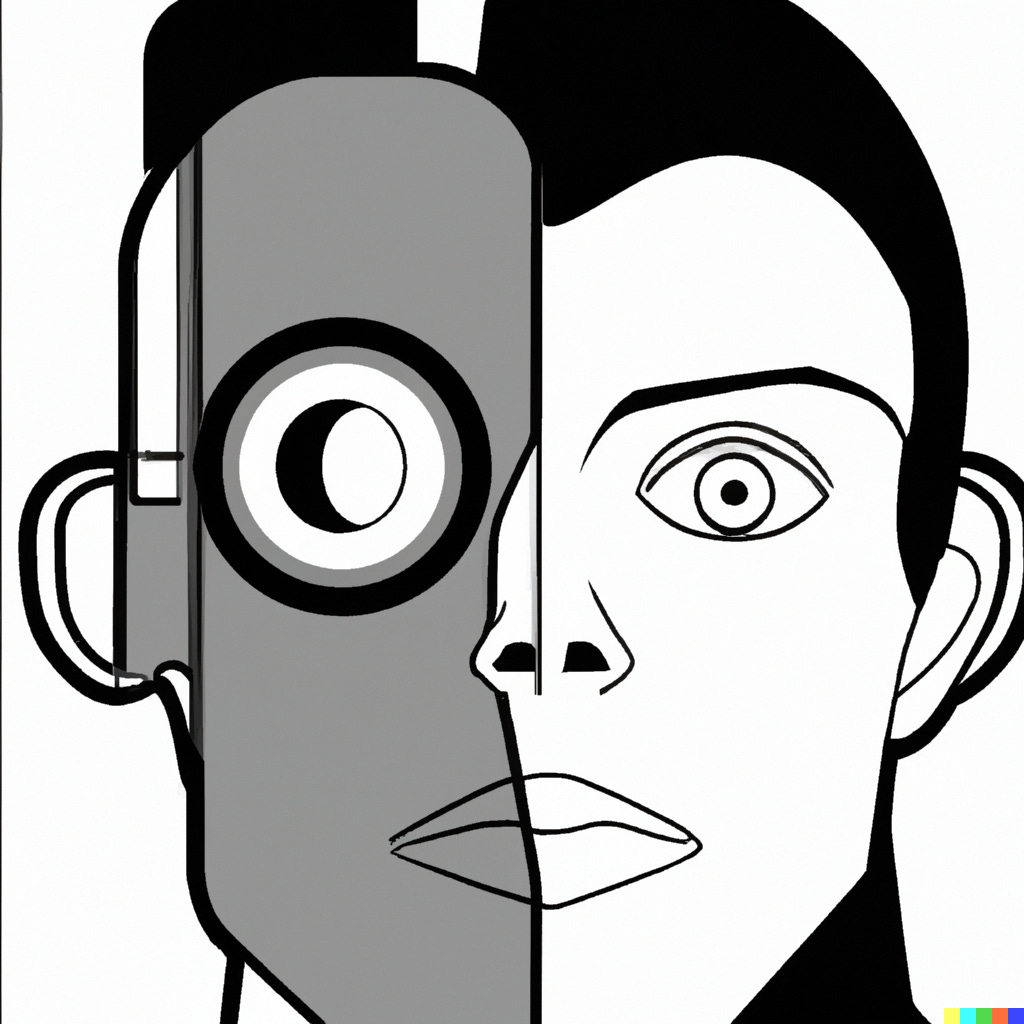

The ability to grapple with discomfort is what makes people truly independent. Gen-Z, I worry, has a minimum threshold of discomfort that is extraordinarily weaker than past generations. We can barely even handle the discomfort of being bored — iPhones satisfy the discomfort of our boredom in milliseconds. Social media has caused us to grapple with fear of missing out all the time, but such a discomfort is trivial and immediately solved upon opening our socials apps. We are used to having less to deal with, and in doing so are becoming beings who succeed conditionally. What once was so great about humanity was it’s unpredictable, unconditional nature, where nothing could stop the freedom of thought, learning, hunger, energy we were all brought into this world with. With what I’ve seen, and having been born on the higher end of the general intelligence spectrum yet also unknowingly built a cage around myself of limiting what I was capable of, technology has already turned us into machines and stripped our humanity from the inside out.

It’s achieved this through design. Steve Jobs pioneered more than just user-centric experiences and aesthetics: he set off the cannon for giving technology the ability to wrap itself around our psychology and decision making processes so acutely that it’s become a part of who we are and how we act. Great consumer products don’t require users to think; they simply know what they are doing from just being handed it. I’ve longly reflected on this excerpt from his book:

Jobs was stirred by a story, which he forwarded to me, by Michael Noer on Forbes.com. Noer was reading a science fiction novel on his iPad while staying at a dairy farm in a rural area north of Bogotá, Columbia, when a poor six-year-old buy who cleaned the stables came up to him. Curious, Noer handed him the device. With no instruction, and never having seen a computer before, the boy started using it intuitively. He began swiping the screen, launching apps, playing a pinball game. “Steve Jobs has designed a powerful computer that an illiterate six-year-old can use without instruction,” Noer wrote. If that isn’t magical, I don’t know what is.”

- Walter Issacson, Steve Jobs

Jobs made commanding an iPad as intuitive as drinking water. The field of Product Design grew in the ripples that his splash in the world made.

With years and time, websites have become simpler, products more intuitive, the world wide web more seamlessly integrated with us an extension of our brains. Web interfaces went from from 72 pixels to 450+ pixels per inch in the past 30 years. Pages and queries now load in real time. The internet acts at the speed of thought.

Simplify, simplify, simplify! - Henry David Thoreau

Humanity loves simplicity. We don’t love challenges, and for good reason: when we are faced with crossing a river with the option to walk across the bridge of fallen trees or swim through the middle, we choose the bridge. No one needs to tell us to do this. We have the decision pre-programmed in us. Our psychology tells us to take the path of least resistance — for if we do not, we will use excess energy that must be saved in case our next hearty meal is days, or weeks, away. Our psychology is programmed for starvation and energy preservation. When peeled 10 layers back, we must always take the easy way out if it exists.

Similarly, if there is no easy way — if a tiger is hunting us and crossing the river is our only option to escape to safety — we will take it. We would run through fire if it meant avoiding becoming prey, or if it meant catching the deer that would keep us alive to see the light of another day. We are programmed to avoid challenge, but when challenge is the only option, our second gear kicks in: do whatever it takes to survive. We would put ourselves a hair away from death if we have to do get it done.

This nature was buried 10 layers deeper than my lowest point growing up. I added stress onto myself to elicit the feeling of scarcity, which elicited my best performance in school. But when tasked with a real problem, when the tiger was on my tail and there was no bridge to cross, I didn’t know how to swim — and I didn’t have the wherewithal to teach myself on the fly.

The problem that forebodes America is that people rarely experience fight or flight. Technology has given us optionality, and our lives are ever more cushioned for it. We have access to cornucopias of food and water called grocery stores. We can travel across the entire world in a matter of days if we want to. We don’t depend on hunting for our lives anymore; we depend on money. We’re an extraordinarily adaptable species. From birth, we take our scaffold of principles — the hunt, the path of least resistance, every human nature quality — and wrap it around the technology that we’re presented with, unknowing that doing so is also wrapping technology around us, and shaping our mind and the way we dictate our society. We’ve adapted to taking paths of least resistance as a god given right, settling for a life of comfortable levels of discomfort only.

I had decided on my greatest discomfort grades in K-12. Technology had an impact on this, but so did the society who utilized it to create a better quality of living, one that accidentally had seemed to cement expectations for the greatest challenges I could face and overcome. I knew I was smart, but judged this only on what I could see on the horizon. When I entered a level above, not yet even in the real world, my operating system gave out. Without knowing it was happening, I was programmed out of my instinctual ability to survive.

I can’t blame my species in our quest for betterment, and observe that betterment has meant abolishing effort. We began technological reprogramming when the first intentional seed was planted in the earth to yield farming, the first step on our path to 0 resistance living. As our technology has become more sophisticated, our species has adapted around it, our culture has consistantly reprogrammed our children out of their mammalian instincts to become “civilized” beings, and now, as technologists have identified how to play with to our emotions in order to sway our outward actions, the very definition of humanity has become so intertwined with the technology that takes on the needs of survival for us. The government are not our nation’s overlords; the overlords are the ones responsible for the shot of excitement you get from a like on your post.

Our technological society has made us into cyborgs, already.

I didn’t know this when I was a student, but I know it now. And I finally realized why Common App college essays would index on telling the story of a hardship you experienced: because hardship, true hardship, may be the only way to regain the killer instincts we’ve been conditioned out of since birth. In my work as a venture capitalist, “killer instinct” is an overused phrase often used to describe a characteristic we look for in people starting companies, because to start a truly generational company, you’ve already had to have broken the gears placed into your brain since birth and rely more on yourself, your confidence, your belief that you are the person to succeed and dictate your own future. You’ve had to become human again, and from the vantage point of a human, you can see clearly how to manipulate technology and minds of users to build product that people will fall for, and pay for. For the first time in our history, having godlike capabilities to control the minds of men is reached upon becoming more human.

What does such a stark fact mean for the future of us as a nation, as America, as a species? When will we give technology the credit it deserves of having already pervaded our brains, our nature, our very sense of being? How many other free thinkers will only operate at a relative maximum, as I had when I was in high school, just to find out in college that I was incapable of truly doing whatever it would take to embrace discomfort and become a diversified, dangerous, and forceful scholar?

I suppose pieces such as this are meant to wrap up on some kind of conclusive point. Here is my best attempt to summarize the points made in this article which was supposed to be a reflection on my educational journey before another part of me took over:

To choose to verticalize when options are plentiful is to choose to not grapple with discomfort. To realize that options are always plentiful, that you can always carve out whatever kind of life for yourself that you want without needing any baseline domain knowledge is the first step to enlightenment.

Enlightenment, in the modern age, is simply a return of what it means to be human. I believe that we are all neutral beings by nature, with godlike capabilities yet demons within us. Because technology has not only made it easier, but also preyed upon our 7 sins to create users out of us, and nature prescribes paths of least resistance, this is the path most choose in our modern day society.

To become a scholar is to reach into your cyborg membrane and strip the wiring within yourself. Embrace discomfort. Do things that don’t come easy to you, and do whatever it takes to see the learning of those things through to completion. For me, this was surrounding myself with a tribe who’s inspired me to view learning as an uncapped continuum. For others it might be different. Do whatever it takes for you to fall in love with discomfort, to always feel like the consequence of being stationary will be being eaten by a tiger. Fail to do this, and the last Renaissance Man to walk the earth may come sooner than expected.

I am proud to call myself a reawakened scholar, though this did not come with a healthy amount of un-conditioning for me to truly embrace the beauty that is stupidity, the growth that can only be accessed via putting ourselves in uncomfortable situations, and the fact that the only thing stopping us from harnessing the power of the universe are the limits we decide for ourselves. In order for us as a species to move forward, I believe we need to realize the evasion that technology has had upon our ability to grapple with discomfort, re-invigorate our instincts, and embrace confidence as they key to become more than we think we are. The preservation of the American Dream depends upon it.